At the heart of Africa’s modern media conversation lies a paradox: a continent rich in oral tradition, culture, and creativity yet underrepresented in the global digital narrative.

That contradiction was front and center at the Africa Broadcast Convention (East Africa), held May 27–28 in Kampala, where I joined fellow thought leaders on a panel titled “Rebalancing Africa’s Narrative: How Technology Is Shaping African Content Discovery, Delivery and Value Creation.”

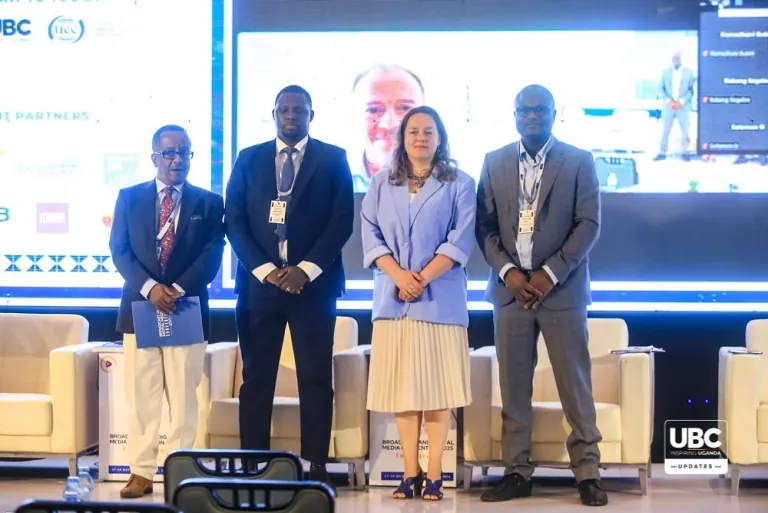

Convened by Broadcast Media Africa (BMA) in collaboration with the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), the event was graced by Her Excellency Vice President Jessica Alupo and the Executive Director of UCC, Hon. Nyombi Thembo. I had the privilege of speaking alongside a dynamic panel that included: Ramadhani Bukini, Director General – Zanzibar Broadcasting Corporation (Tanzania), Viktoriia Budanova, Director, Africa – Sputnik (Russia), Daniel Belayneh, CEO – Arts TV (Ethiopia), Hamid Ouddane, Founder/CEO – Babeleye (Egypt) and Myself, Robert Sebunya, Chief Executive – Ten-X Holdings.

The Challenge: Africa’s Voice in the Age of AI

Africa is entering a digital age shaped by artificial intelligence—but with data, language, and infrastructure rooted in a colonial past. For over a century, Europe and the West have built institutional knowledge systems: monastic schools, printing presses, early universities (like Bologna in 1088), and eventually machine-readable archives that fueled digital evolution. In contrast, Africa’s formal education systems emerged mostly in the 19th century, often via missionary schools like the Church Missionary Society in Uganda, Ghana, and Nigeria.

This late start means our historical memory exists largely in oral form—not in digitized repositories. Africa has over 14,000 radio stations, including 264 in Uganda, over 500 in Ghana, and more than 600 in Nigeria—yet the majority of this audio data is not archived, tagged, or transcribed. What we risk losing isn’t just culture—it’s raw data that could power Africa-trained large language models (LLMs) in the future.

The AI Bias: Models Trained Elsewhere, for Others

The AI that’s shaping tomorrow—ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, LLaMA—is largely trained on data from the US, Europe, and China. These models understand European political systems, US pop culture, and Chinese history with remarkable fluency. But they stumble on Luganda proverbs, Acholi folktales, or Swahili metaphors.

That’s because Africa’s languages, accents, and storytelling patterns are underrepresented in the foundational data. Worse still, even among major African languages, there is fragmentation: dialects shift across borders, and transcription is inconsistent. Without substantial investment in African language datasets, the continent risks becoming digitally invisible in its own AI future.

And it’s not just about language—it’s also about infrastructure. Audio AI models require significant GPU processing power and storage—resources that are expensive and rare across African institutions. Even Europe, despite its wealth, has only recently begun developing indigenous AI audio models. For Africa to leapfrog, we need our governments and private sector to invest in GPUs, local cloud capacity, and open-data repositories that prioritize African voices.

Leapfrogging Through Mobile, But at a Cost

Despite these constraints, Africa has had a mobile-first digital journey. Over 90% of internet access in sub-Saharan Africa comes through smartphones (except South Africa at 76%). This unique path has unlocked services like M-Pesa, which recorded over 28 billion transactions in a single year, contributing to $309 billion USD in mobile money value in Kenya alone. But here lies another paradox: while we are digitally connected, our software and platforms are imported—from the apps we use to the algorithms that curate our content. Africans are consuming, but not designing, the frameworks that shape their perception of the world. Technology without agency reinforces dependency.

The Cost of No Archives: A Lost Generation of Wisdom

Our grandparents told stories under mango trees. But oral tradition—while rich—isn’t searchable. It’s not trainable. Without archiving our radio broadcasts, podcasts, community theater, or even TikTok skits, we create a generational disconnect. The young can’t learn from the past if the past can’t be indexed. What Europe achieved through the printing press, Africa must achieve through audio preservation, digital transcription, and open-access archives.

Hope in the Gaps: COVID-19 and Digital Acceleration

Paradoxically, the COVID-19 pandemic became a blessing in disguise. As lockdowns swept across the continent, even the most traditional sectors adopted digital tools out of necessity.

Africa gained 10+ years of digital transformation in under two years. Suddenly, e-learning, Zoom diplomacy, online radio, and digital remittances became standard. This momentum gives us a rare opportunity. We can choose to shape a digitally sovereign Africa, not just by building apps—but by training models, curating archives, and defining standards that reflect our values, languages, and complexities.

Conclusion: From Oral to Algorithmic – The Future is Ours to Code

Africa’s story won’t be rewritten in a European textbook. It will be shaped by what we choose to document, digitize, and design.

The future of African storytelling requires a new infrastructure:

- Cultural datasets that preserve nuance

- African-trained AI models that understand local expression

- Policy frameworks that empower local innovation

- Public-private partnerships that fund GPU access and data sovereignty

We cannot rebalance Africa’s narrative without reclaiming our data, reshaping our algorithms, and reasserting our agency. Let’s not just talk about Africa’s future—let’s code it.